According to Lorin Schwarz, arts-informed research "holds within it an imperative not only to question its own completeness and objectivity, but also to 'speak back' to forms of authority that have traditionally silenced and left out voices that either don't fit, refuse to offer a definitive answer or that demand emotional knowing in order to understand what they feel compelled to say" (29). Schwarz, in her article "'Not My Scene': Queer Auto-Ethnography as Alternative Research Method." argues that research can benefit from this type of methodology.

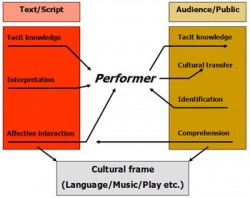

How does one reflect on something as profound and somewhat mind-boggling as the concept that some topics are enhanced by this type of methodology? When I contemplate this method, I envision this diagram that I found online: With this type of research, things that would otherwise be left unnoticed are brought to light: the "human" elements that are not, scratch that, NEVER black and white. Schwarz argues that this type of research "provides a critical foundation to question the structures we take for granted in often unexamined dualisms of 'black and white' thinking" (29). Humanity, when viewed as black and white, becomes this rigid, unbending thing that breaks when the slightest pressure is put on it. This type of research allows the researcher and the audience to see things in shades of gray.

Schwarz demonstrates her arts-informed research with a play. A one man act that explores what one man feels when he sees other happy gay men together. This is the type of auto-ethnography that perhaps no other type of research can get at at this depth. Some of the passages get at the depth of human existence in a way that regular, black and white, research never could.

"What we call 'the closet' springs from the idea that identities are waiting to be discovered and unfold from the inside out. Authenticity hinges on erasing the traces of others from our work to become who we 'really' are. To leave the traces of social interaction visible is to compromise our claims to authenticity and self-determination" (Gray 2780-2796).

Chapter 5, "Online Profiles: Remediating the Coming-Out Story," of Gray's Out in the Country speaks to how media, particularly the internet, plays a role in LGBT identity. The above quote, for me, pretty much sums up the chapter. Identities don't just suddenly unfold from the inside out. Identities are socially constructed. Rural LGBT youth are aware of their sexual desires but finding "realness" for these identities and desires can be difficult.

Therefore, many turn to the internet and to sites like Gay.com to read real coming out stories and to give voice and meaning to their desires and feelings. They often do not know the terminologies used to express what they are feeling until they search the internet for sources to help them understand. So rather than the internet being a place that "turns them" or puts ideas into their heads, it is a place that helps them understand and come to terms with who they are. It is a social place that helps make it all real.

I've often wondered if having a resource like the internet would have helped me come to terms with and embrace my identity much sooner than I did. I fought against my own feelings for years and refused to knowingly place myself in social circumstances that would bring those feelings to the forefront. Perhaps if I would have had the internet, a place where I could have researched and learned in private, things would have been different.

Bottom line is that media is a positive resource for many rural LGBT youth, helping them to learn and understand who they are, making their identities real!

"If rural LGBT-identifying youth are at times hard to see, it is as much because researchers rarely look for them as they have so few places to be seen. They must also be strategic about how they use their communities for queer recognition if they are not to wear out their welcome as locals" (Gray 1867-1883). And this is what chapter 4 of Mary L Gray's Out in the Country deals with: the spaces that rural LGBT folks occupy to become both visible and to work on identity.

Gray makes a good argument for the visibility of LGBT youth in rural communities. But we don't drive down main street, rural town, USA, or the town square and say to our friends, "oh look, there's Billy Bob or Sally Sue at the gay bookstore. I never knew they identified that way!!" And why is that? Well, unlike in the cities, it'd be kinda hard for Billy Bob and Sally Sue to support a gay bookstore in rural town, USA!! And yes, there are probably more than two queer identifying folks in rural town, USA, but it's likely that Billy Bob and Sally Sue are the only two of the dozen or so that do exists that have the couple of extra bucks that they could spend on such luxuries.

So what visibility can rural LGBT possibly have in rural town, USA? Gray describes what she calls boundary publics. Places that are not typically seen as queer spaces can become that when LGBT identifying individuals choose to meet there. Gray argues that "boundary publics therefore should not be seen so much as places but as moments in which we glimpse a complex web of relations that is always playing out the politics and negotiations of identity" (1900-1916). Gray goes on to note that "rural young people make space for themselves through acts of occupation" (1980-1996). Examples she list include doing drag at the local Wal-Mart Superstore, attending a church skate park punk rock concert, and through new media such as websites and blogs.

The point is this: rural LGBT youth, and adults too for that matter, make the space for themselves to be visible. It's not like the locals don't know who is LGBT! Seems that people in my home town knew I was a Lesbian long before I even knew what the word meant. And the fact of the matter is that those who are gay, lesbian, bi, or trans in rural communities are not hiding any big secret. Sure, they don't go around flaunting it because that could do more harm than good, but as one rural youth told Gray "I think everyone knows about me [being gay]. I don't really have to say it" (2090-2106). So if a group of queer identifying people are seen in one place, that place becomes, for the moment, a place for them to be visible as LGBT.

The concept of boundary publics and spaces such as the local coffee shop becoming a place of identity work are new to me. Gray discusses several theorists who deal with the traditional notion of the public sphere and how her boundary publics fit into these theories. Since I am unfamiliar with these theories and theorists, it is hard for me to wrap my mind around all of this on one read, but I believe I have the basics of the concepts: public spaces are plastic enough to stretch and become something they are typically not.

Rather than to split the chapter's up and blog nightly, I have decided to combine the two post together and do them every other night, allowing me to keep the chapters together. No internet in Philly last weekend and illness this week have me slightly behind. That being said, it's time to move on to chapter 3 in Mary L Gray's Out in the Country.

This chapter, entitled "School Fight!", basically chronicles the attempt of students at Boyd County High School to establish a Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) club at the school. They were turned down numerous times for technical reasons but finally managed to get it approved by involving the ACLU. It wasn't long, approximately two weeks, however, before the school board voted to do away with all clubs at the school. This was seen for what it was: a ploy to do away with the GSA via the backdoor while the other clubs continued to meet.

It wasn't until there was a Unity Rally held that things finally came together. I liken it to the way my family feels about things. . . I can bad-mouth anyone in my family I want too, but let someone else try bad-mouthin 'em and it's likely they will have a fight on their hands. I've learned that this is also the way rural communities work. We can fight amongst ourselves and bad-mouth each other all day long, but don't let no outsider come in and try to spread hate and discontent. This is what happened in this small community as well. During the Unity Rally, while they never exactly embraced the concept of the GSA, it "proved more solidifying than anyone anticipated, thanks in no small part to notorious Kansas-based Westboro Baptist Church minister Fred Phelps" (1668-1685). As one participant stated, "I thought it was important to show these folks from Kansas that a message of hate and intolerance is not something that people in Eastern Kentucky believe" (1685-1703).

Eventually, the ACLU did have to become involved in the situation and they sued the school board, who did not even have the power to decide about clubs in the schools. The case was won and the GSA was once again established in Boyd County High School.

Gray notes that "the situation called attention to the complicated intersection of racial and class tensions that structure rural life" (1721-1737). In areas where people are struggling to find jobs and keep their families fed, clothed, and housed, the thought of any group getting special treatment is threatening. Rural communities are also threatened when groups such as the ACLU become involved. They feel that these urban influences sweep into these rural communities, disrupt everything, then rush back out leaving a mess in their wake. And often, they have a point. But as this example clearly shows, if faced with embracing the queerness that is family or allowing those from Kansas to spread hate among their community, they chose to embrace their own.

Jessica Fields "raises the critical question of whether 'looking like everyone else' is an accomplishment or a derailment for progressive LGBT social movement and identities and, ultimately, decides it is a setback" (Gray 1068-1084). As I suggested last night, Gray argues, however, that "the conversation in rural communities hinges not on whether LGBT youth look like everyone else as much as do they live here at all" (1068-1084).

The second half of this chapter is a continuation of one rural communities struggles to educate their community on LBGT youth. One woman's (Mary's) efforts to hold an educational meeting, sponsored by the Homemakers Club, was fraught with problems. The room they had reserved for the event in the court house suddenly got canceled by the clerk , who claimed that Mary had booked the room under false pretenses. The newspapers scheduled to cover the event were getting threatening emails and phone calls, and Mary also received threats.

Mary feared that the event would be poorly attended due to the change in venue and the problems they were encountering, but the night of the event found "an overflow crowd piled into the . . . Library's Children's Reading Room for more than two hours of discussion" (1162-1177). There were 43 people there that night, and most were eager to hear what the panelist had to say. There were a hand full of those that tried to change the tone of the meeting, but they were unsuccessful.

After the meeting, Mary resigned her position in the Homemaker's Club, telling Gray that she would "not spend the rest of [her] life with a bunch of people with such closed minds" and that she would "write all of the UK [University of Kentucky] Advisors and let them know about the word 'discrimination' and how [they were] treated from the top of the Kentucky Extension Homemakers Association . . . from the logos to nonsupport from agents" (1225-1240). Even a successful meeting took its toil on the people who were trying to give the LGBT youth in the community visibility.

So while 'looking like everyone else' may seem like a cop out to some in the LGBT community, for these youth it means at least being acknowledged, of being seen as an individual, which is something that Napier was unwilling to even admit. Again, walk before we run.

"Son, I'm sorry, because I know you don't agree with me on this. But I don't believe in supporting gay people's rights, because it's bad for families" (qtd. in Gray 819-835). Yes, you read that right! That was Kentucky Representative Napier's response to a 17 year old college student who had presented him with 400 signatures on index cards of LGBT individuals to prove that they did exist in his district. And this was in 2002.

It's always amazed me that there are those that believe being gay or lesbian is somehow detrimental to family live. I have a family . . . I have a partner, a brother, a niece, two great-nieces, a mother, a father, and probably some assorted cousins. Is that not a family? My partner and I could have had kids, could have adopted, could have done foster children . . ., God knows there are plenty of unwanted kids in this country.

The first part of this chapter in Mary L. Gray's Out in the Country discusses one attempt of making LGBT youth more visible in one rural area of KY. Gray argues that "family is the primary category through which rural community members assert their right to be respected and prioritized by power brokers like Lonnie Napier" (835-851). By invoking the "we are the same as everyone else" they hope to become visible within their own communities. They can do this by claiming familial ties to the community in which they live.

This, of course, is a throw back to the argument that we, as LGBT, are the same as everyone else and capable of upholding the social norms of society. I've read a lot about the different arguments that exist for LGBT communities in the last year, and I would argue that perhaps people in rural areas have to be accepted as "normal" before they can become anything else. One has to be visible before they can begin to push the boundaries further. Perhaps there is more meaning than I thought in the old saying that you have to walk before you can run!!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed